India as a country, has a rich tradition of textiles. Today, Jaipur in Rajasthan and Ahmedabad in Gujarat have become international hotspots for handloom and khadi Indian made fabrics. Textiles are a living history book. They are a window into a countries history and culture. To understand the importance of Khadi, first, we need to explore its evolution. The art of handloom and Khadi has helped India to gain independence and shape it into the country it is today.

Handloom and Khadi Fabrics are a Living History Book

Over the last seven decades, India has become a powerhouse for hand-woven textiles that is unparalleled to anywhere else in the world. Through this time India has seen constant innovation. Change is seen in technologies, the design of patterns and motifs, and the global expansion of the industry.

To understand how khadi has evolved, first, we need to understand how traditions and influence have evolved in India. Many people believe that traditions are static, passed down from one generation to the next. With, a set of strict rules that artisans must follow. This is not true. The handloom and khadi industry has seen influence through history by its surroundings and the culture of the time. Such Influencers include: political, social, economic, and even science. Because of this vintage handloom and khadi fabrics act as a history book

Academics who spend their research money studying and privately curating handlooms and khadi have traditionally been the ones who study textiles. Today, we are seeing a shift into the public interest in learning the history of Indian textiles.

An Evolution

Today the handloom and khadi industry struggles to survive. And, all too often, we see artisans being taken advantage of by foreign businesses. In order to understand the state of the handicraft industry today, we must first look at it's past.

Khadi started during The National Movement. As India fought for independence from British Rule, khadi and cottage industry crafts were born. After India received independence, a new, more modern style of design took effect as artisans positioned their products for the global market.

These artisans all but disappear after the introduction of the power loom. Today, there is a resurgence of the handicraft industry. In which we need to look at the roles of the craftsperson, designer, and artist, and what that means to the people of India. And finally, handloom and khadi has now become a fine art medium.

Khadi as a nationalist movement

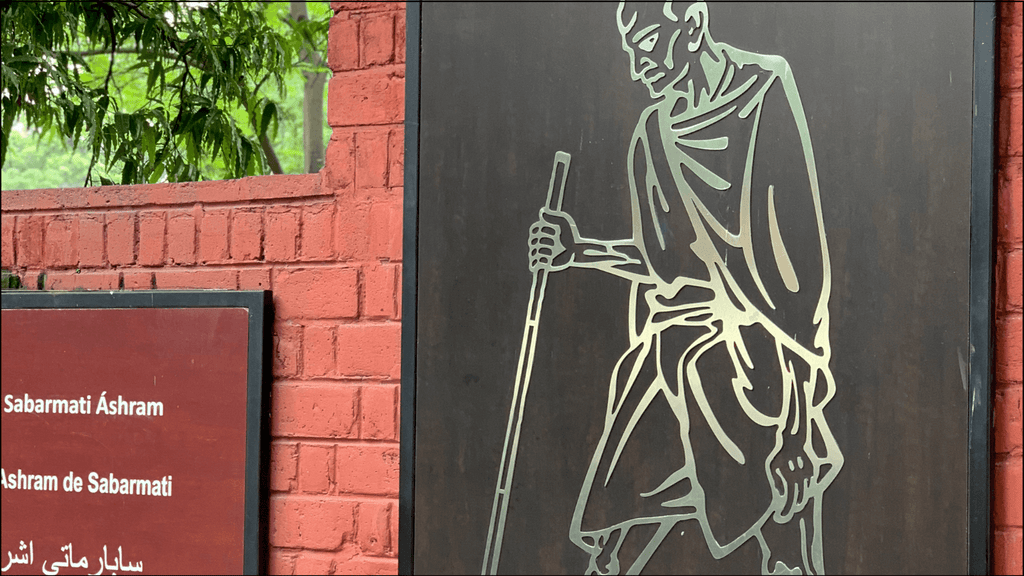

Photo taken at the entrance of Mahatma Gandhi Ashram at Sabarmati, Ahmedabad, Gujarat

The handspun and handwoven fabric was named khadi by Mahatma Gandhi. Because of the fabrics, rich history during the time of British independence in the early 20th-century khadi has become a symbol of India's freedom. Gandhi encouraged Indians to turn to handicrafts in order to become self-sufficient and boycott British imports. Khadi continues to play a part in India’s politics. To this day, India makes all national flags out of khadi.

During the time of India’s independence textiles that reflect Swaraj, Swadeshi, and grass-roots development are seen. Authentic khadi from this time period is course and heavy fabric that is hand spun and hand woven from cotton fibers.

Swaraj is a Hindi word that means “generally self-governance or "self-rule", and was used synonymously with "home-rule" by Maharishi Dayanand Saraswati and later on by Mohandas Gandhi, but the word usually refers to Gandhi's concept for Indian independence from foreign domination.”

Swadeshi, refers to the Swadeshi Movement. “The Swadeshi movement, part of the Indian independence movement and the developing Indian nationalism, was an economic strategy aimed at removing the British Empire from power and improving economic conditions in India by following the principles of swadeshi which had some success.”

During The Nationalist Movement, khadi saw it’s first evolution from European influence. This can be seen in brocades made in Varanasi between the 19th and 20th centuries. The designs began to move away from images of traditional Indian plants and started to incorporate European motifs and patterns. These new designs mimicked the international art movements of Art Deco and Art Niveau.

what a more western aesthetic means to india

This influence seen in khadi textile designs at this time of independence is symbolic of the new Indian identity. It is of a country that saw influence from the West. By studying the new aesthetic of khadi at the turn of the century, we are really studying the impacts that European rule had on the country and the new culture and traditions that emerged as a result.

This time period of independence is also important because it marks the first time the cultural practice of caste was seen differently in Indian culture. Weavers who were creating fabrics that were symbolic of their caste and place in Indian society, were instead designing for a Pan-national movement uniting all Indians against British rule in order to gain independence as a country.

Modernism... In Art and Manufacturing

During the post World War environment and early decades of Indian independence, India became influenced by Europe and North Americas Modernism art movement. Bold geometric shapes and more modern methods of manufacturing would characterize the art movement of the time. The trend of Modernism is also visible in major cosmopolitan cities architecture at the time.

a modern nation

After becoming an independent nation, India moved confidently. The government and private donors began to donate resources to build infrastructure. New ambitious buildings were commissioned and built. Schools and educational facilities that focused on disciplines like design, management, scientific research, and engineering were developed. As cities began to expand debates started to arise on the effects on Indian culture and the best model for international growth.

Along with this movement towards a new modern India, the textile industry saw a shift from handspun handwoven handicrafts to power loom made textiles.

During this time, the textile industry would experiment and play with how they made fabrics. They were also trying out new fiber technologies. Investments were made into initiatives to revitalize rural economies and artisans. The government created programs that lead to the emergence of private entrepreneurship in garment manufacturing, home furnishings, and lifestyle companies and brands. India began to look outward to exports, with heavy influence on Europen design needs. And, with that goal in mind textiles saw a shift towards mass-produced West-centric Modernism marked by geometry, abstraction, and colour.

The Modernism movement pushed Indian textiles into an age of rapid mass production made possible by new technologies. Today in the 21st century, this period's influence relevant. And, the companies formed during this time grew into some of India’s largest international conglomerates that are still operating today.

A Return to Traditions

Today, traditional cotton khadi spinning and weaving is a dying art. It has managed to survive in very small rural villages - in areas of Bengal, Orissa, Andhra Pradesh, and Telanga. These handloom and khadi communities live nomadically in geographically harsh conditions.

fabric for the elite

Khadi, which was once a fabric for all of India, instead, today, is a representation of the finest Luxuries. Craftsmen are now spinning khadis with silk, wool, and other modern synthetic fibers like modal have become popular because of market demand. Khadi fabric is expensive. Today, the people that are the ones weaving it are not able to afford it themselves. They must resort to wearing cheaper mass produced power loom fabrics.

The push to reestablish the traditional handloom and khadi industry has been met by both accolades and criticism. At the root of the argument, we must first identify the difference between the craftsperson, designer, and artist.

As India continues to evolve so does the role of craftsperson, designer, and artist. With the introduction of design education into Indian curriculums in the 1960s, the art of design became the main focus in textiles. Historically, the design component has been a way to add value to the craft aspect of weavings technical know-how.

No longer the voice of a nation

As the cottage industries are reborn, there is a growing divide in the hierarchy between the profitable “creatives” and the “skilled” weavers.

What is interesting about this system is that it makes the designer necessary to the craftspersons survival. Designers are tastemakers who have their fingers on the pulse of that latest international as well as national trends. This new trend of the international designer has marked the degradation of textile design developing naturally over generations and influenced by the current times of the country. Instead, weavers force their design to meet foreign market pressures. The fabric no longer reflects India's current culture, but instead the needs of the West.

Today we see an influx of Western designers who dictate what the craftspeople should make, capitalizing on their low cost of labor. They then return to their home countries to sell the goods for much more than they paid. Is this ethical?

There is another fundamental divide in the handloom and khadi industry. That divide is between designer and artist. Designers create with the purpose of function. They want to make things that have a real use. Artists that use handloom and khadi weaving as their medium are following their creative bliss. They are exploring philosophical or aesthetic ideas that may not address a real need.

Again, we see that those who physically make the art remain unknown, while society celebrates the artists vision.

Khadi the fabric that became famous in India for uniting and creating independence is now a symbol, for some, of classism.

textiles without hierarchy

But, there is a new growing group of textiles artists in India. Ones that blend the idea of the craftsman, designer, and artists. They shift between roles. Their focus varies between handmade fabric expert, to the researcher, to fashion designer. This new groups of textiles designers range from traditional reproduction to entirely new ideas, and everything in between. Their pieces often blend old and new together and tend to reinterpret traditional textiles in a modern way that reflects society as it is today. And most importantly they are sharing credit with one antoher.

Noteworthy artists include Ajit Kumar Das, Toofan Ragai, Jadunath Supakar, and Jean Francois Lesage.

Check it out

If you want to see some khadi history in person, visit one of these places!

Calico Museum of Textiles - Ahmedabad, Gujarat

The Calico Museum of Textiles in Ahmedabad is the premier textile museum of India. For its distinguished and comprehensive collection of Indian textiles, it is one of the most celebrated institutions of its kind in the world. Both the Calico Museum and the Sarabhai Foundation have an extensive programme of publications in the museum.

***pro tip - Entrance into the museum is by appointment only, so make sure to book a tour in advance.

Weavers Service Centres

The Weavers Service Centres have been in operation since 1956. The Planning Commission manages the centers, in order to help cater to the needs of the handloom sector. The goal of the centers is to promote handloom and khadi design.

The objective is to increase product development, technological development, skill development of weavers, extending documentation support, and revival of the industry. There are now 25 centers in India.

Textile Department, National Institute of Design - Ahmedabad, Gujarat

The Textile Design program develops innovative and synergetic approaches to design. The curriculum focuses on cultural heritage, socio-economic and environmental concerns. The students explore and develop these themes through fieldwork and research.

If you want to meet the next generation of textile artists visiting the University is a must.

Mahatma Gandhi Ashram at Sabarmati, Ahmedabad, Gujarat

While at the Ashram, Gandhi formed a school that focused on manual labor, agriculture, and literacy to advance his efforts for self-sufficiency. It was also from here on March 12, 1930 that Gandhi launched the famous Dandi March. A demonstration of 241 miles from the Ashram (with 78 companions) in protest of the British Salt Law, which taxed Indian salt in an effort to promote sales of British salt in India. This mass awakening filled the British jails with 60,000 freedom fighters.

Later the government seized their property, Gandhi, in sympathy with them, responded by asking the Government to forfeit the Ashram. The Government, however, did not oblige. He vowed that he would not return to the Ashram until India won independence.

During the fight for independence from 1930-1933, the ashram became a refuge for freedom fighters. Over the years, the Ashram became home to the ideology that set India free. It aided countless other nations and people in their own battles against oppressive forces.

India won independence on August 15th, 1947. Gandhi was assassinated five months later and never returned to the ashram.

Today, the Ashram serves as a source of inspiration and guidance and stands as a monument to Gandhi’s life mission and a testimony to others who have fought a similar struggle.

Leave a comment